Biographies | Show notes | Subscribe on Apple Podcasts | Other listening options

Motherless Child introduces listeners to Charles Wakefield, Jr. For more than four decades, South Carolina has known him only as a cop-killing double-murderer. Only a handful of people in the state have heard Wakefield’s full story. Almost no one has heard him tell it in his own voice. Wakefield’s story goes all the way back to his earliest memory: discovering his mother had abandoned him. For more, read the show notes or continue reading below for a short essay on Wakefield’s childhood memories.

The kids are there on the curb playing some game, calling each other names, and waiting for the sun to duck behind the buildings and turn to shade.

That’s when the sound rises up off the asphalt and grinds in a mean echo down the street. It’s a mechanical growl, the sound of a rumbling V-8 engine under a steel hood. It winds up, turning over and over until it’s almost a pained whine, and it drives the mirrored chrome bumper down the street too fast for any virtuous purpose.

If the kids look long enough, they’ll see the bubbles on the top of the car. If they look even closer, they’ll see the man with the badge behind the wheel. They could even look in his eyes to see if there is any hope of finding something honorable in him as he drives his foot deeper into the accelerator.

They can’t look that long, because the sound of that engine screaming under its hood is the only warning they will get. In the kids’ minds, if they don’t run, the last thing they’ll see will be their own face in the reflection of the bumper.

So, they run, scattering under cloudless, steam-hazed August skies, finding any direction to run that takes them out of the police car’s path. They cut left and right, zipping like drops of mercury out of a broken thermometer, taking refuge in their mamas’ houses, skinny alleys, or the shade of a plum tree’s branches. They run to anywhere the car couldn’t go.

When they finally stop and hear the car rumbling off to another group of kids on another street, they take shallow, broken breaths and thank God the sun is still up. It would’ve been worse in the dark.

To see it at all, you’re going to have to look though a half-century of history, through a lens of progress and protest, through a lifetime most people didn’t know existed. You’re going to have to imagine Charles Wakefield and his friends as children. You have to imagine, because few people knew him then, and those who did are mostly dead or have long forgotten about that little boy who ran the streets of West Greenville looking for fun or food.

August suns over South Carolina burned the hottest. They turned the air into a steamy, thick soup, the kind that no box fan in a window could turn cool. You could sit in the dark house with your clothes sticking to your skin, or you could go outside and hope a breeze would hit the back of your neck just right.

Wakefield played in the streets, throwing a ball, chasing his friends, and fighting mock wars before they were old enough to get sent to Vietnam. When they got older, they would take to the streets for other reasons. They’d look for girls, shade, or whatever brief relief they could find from a life that they never really got to start.

As children, teens, and young adults, Wakefield’s friends knew the police would come. They always did. It was West Greenville in the 60s, and Wakefield was among a neighborhood full of black kids in a black part of town. Wakefield would remember it like this: the police would drive around looking for somebody doing the wrong thing, and if they couldn’t find anyone breaking the law, they’d amuse themselves by watching black boys scatter in the sun. They’d gun their engines and drive at the kids just for fun.

Not many people can imagine a man distilling a child’s fear into entertainment, but that was the alchemy those kids came to understand. That was West Greenville when Charles Wakefield was a kid.

Even if you know the Greenville, South Carolina of today, you’re going to have to imagine a different place, because other than how the streets are laid out, today’s Greenville didn’t exist when Wakefield grew up there.

Charles Wakefield ran the streets of West Greenville thinking about this woman, one he described as beautiful. She took all of his siblings and left for Florida. She didn’t take her youngest son Charles with her, and at 65 years old, that son still wonders why.

Erase the farm-to-table restaurants, craft cocktail bars, and parks that stay green all year. In your mind, build old clapboard houses where tired old ladies sold beer for pocket change. Tear down the sweeping footbridge that spans the Reedy River Falls and replace it with a slab of concrete called the Camperdown Bridge, a place that not only hid the tumbling falls but everything else that happened in the shadows. Pretend the streets aren’t lined with white string-lights from January to December. Forget that it’s only been a few years since a statue honoring desegregation went up at the corner of Washington and Main. Instead, imagine streetwalkers on the corner, dope dealers in the alleys, and police who used cars to chase children off the street.

The way Wakefield looked at it, the police weren’t trying to kill the kids. Wakefield believed the cops were trying to teach the kids a lesson.

The police, as Wakefield saw it, wanted the kids to learn to run.

Wakefield thought police wanted the kids to learn the lesson while the sun still shined. Lessons learned early stick with a man, and by the time Wakefield was old enough to spell his name, he knew to make tracks when he heard one of those big engines in the street.

Wakefield was one of those kids who ran, and he always knew it would’ve been worse if he’d been running after sundown.

Wakefield was often thankful that the cops had been white, because not only was it worse when it got dark out, but he said it was worse when the police were black. In 1963, Greenville hired its first black police, and somewhere along the way, as Wakefield saw it, those black cops decided it would be better to be harder on the black kids than the white police were. The last thing Wakefield wanted to see was a black man with a badge coming up the street.

Even at age 65, Wakefield remembered one cop called Brownlee, a guy Wakefield described as a big, bad black man with a badge who struck sheer terror into every black kid in West Greenville. Wakefield and his friends ran the fastest when they were getting away from Brownlee.

It would be too many years before the West Side’s streets had a big ballpark for its Red Sox affiliate, bike-powered rickshaws, and busking singers with tip buckets. When Wakefield grew up, the streets stayed dark at night.

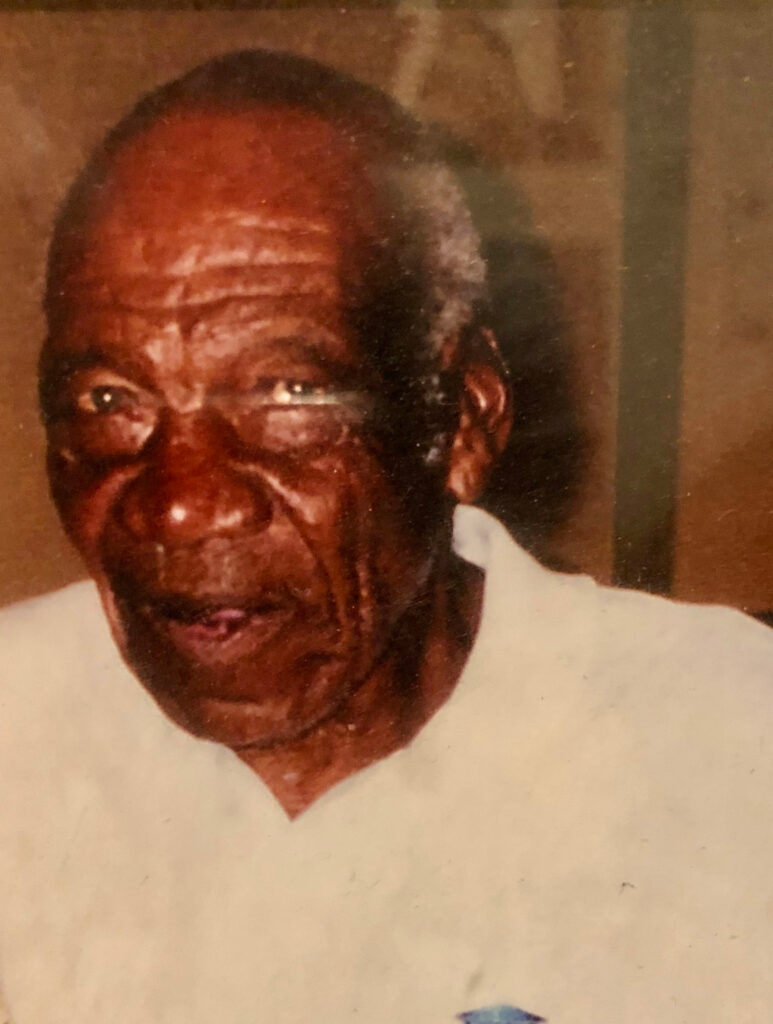

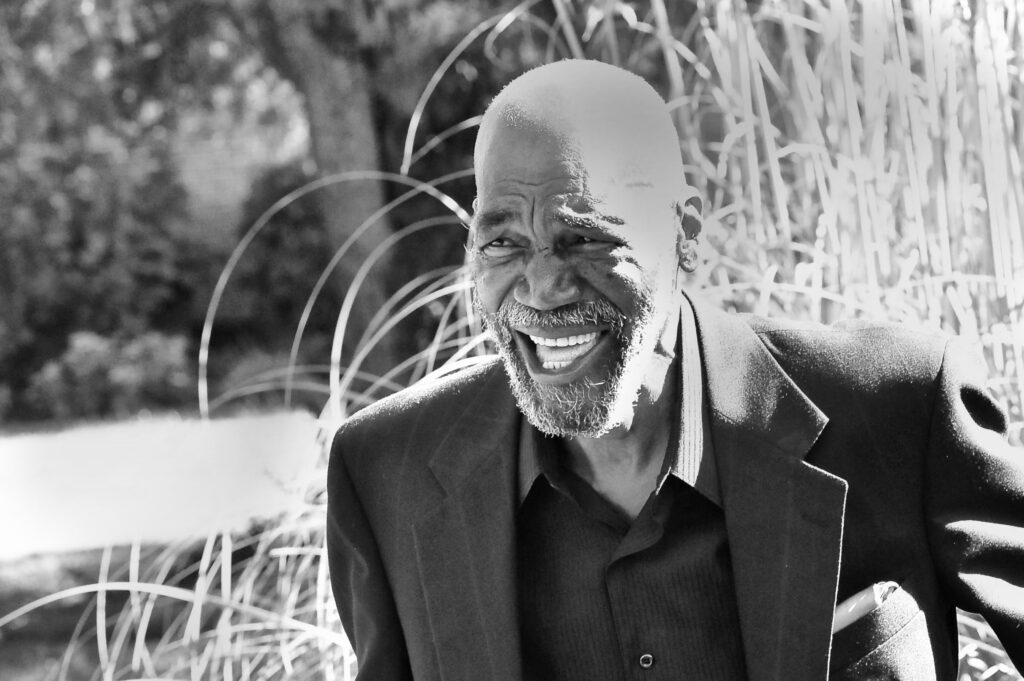

Wakefield’s mother

Wakefield’s ex-wife and daughter

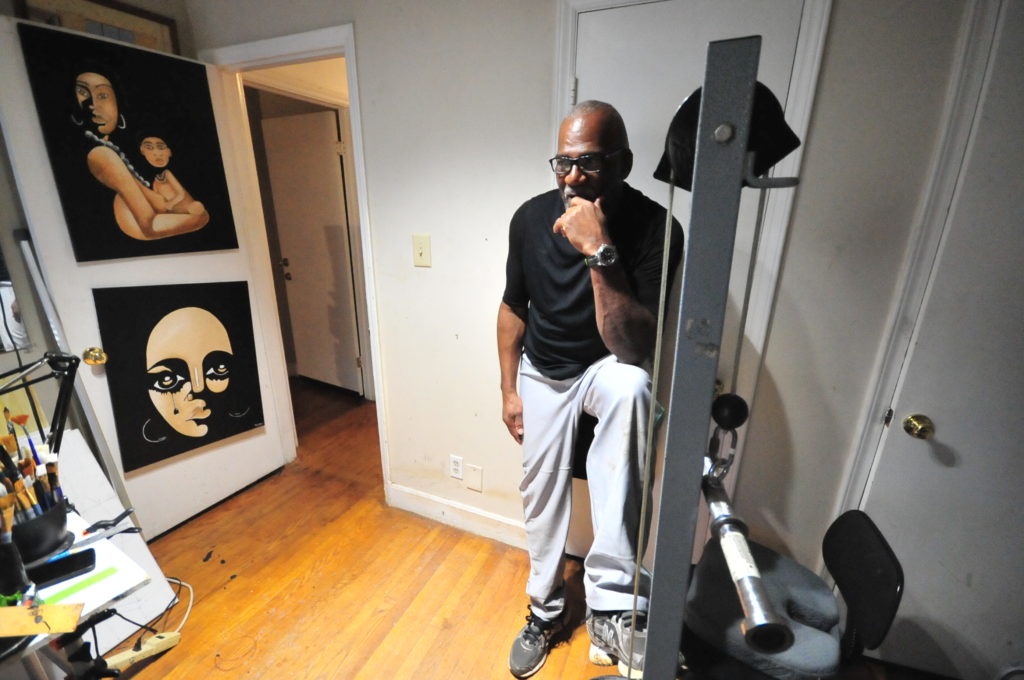

Wakefield’s father

Wakefield’s stepmother 2018

Wakefield could have stayed in his bed at night, sweating into a mattress until it was time to get up and get chased down the street again. But, why would he? A night breeze in the middle of a South Carolina summer may be the sweetest relief a man can find in West Greenville, even if it happens in the shadow of night where all sorts of relief are found.

Wakefield did not go home when the sun went down, and that was how he learned a different lesson altogether. If he stayed out too late, he wouldn’t be afraid of the screaming police car engines. Instead, he would hear the slap of the cops’ boots against the pavement.

The police had taught Wakefield to run when he was a child. Long before Bruce Springsteen ever wrote his song, Wakefield and his little friends in West Greenville were born and raised to run. As kids, they scattered into the sunshine, and by the time they were teenagers, they ran into the darkness. Those same police who taught the kids to run were chasing them as teens and young adults. Wakefield said it would happen even if they’d done nothing wrong. They would run anyway. That was as good as breaking the law, and that was good enough for a trip to the city jail.

There were a lot of lessons a kid could learn in West Greenville, and learning to run was one of them. One of those lessons, Wakefield learned much too late.

There would come a day Wakefield would believe that the worst of the police didn’t come rushing up in their police cars or pounding their pavement with their boots.

Wakefield came to think the worst of the police crept up in the shadows, taking small steps toward a collar that resulted in more than a fine.

Wakefield finally couldn’t run anymore, and he spent 35 years in prison.

Show notes:

Motherless Child opens as Charles Wakefield, Jr. listens to his sister, Vanessa, sing. He is calm and unbothered, until the sun starts to set and he realizes it’s about to get dark in Greenville, SC. He gets out of town before the sun goes down, and begins to tell his life story.

His mother leaves him and takes his siblings away to Florida. His beloved grandparents die, leaving him with only an alcoholic father who takes him to illegal bars. Wakefield finds a new life when he marries and has a daughter, but he quickly lets it unravel as he repeats his father’s mistakes. Before long, he ends up on Death Row, leaving behind the rest of his loved ones, people who die one by one as he sits behind bars. Given a chance to clear his name, Wakefield promises God he won’t stop working to prove his innocence.

Featured interviews in Motherless Child

4 comments on Episode 4: Motherless Child

Comments are closed.

Not a dough at all in my mind ,” Charles is a innocent man ” – I sit here hoping by the end of these episodes Names will be exposed that took part in ” Set Up ” , I know of one who has died & I believe there are others still living & even more although not directly involved , know exactly Why Frank was shot / Charles was just an easy Target to blame

Incredibly intrigued by this series. In the end I hope justice is shown to whomever is responsible for the deaths of two people.

Oh my goodness, Ms Vanessa’s voice is a joy to hear!