Biographies | Show notes | Subscribe on Apple Podcasts | Other listening options

Frank Looper made himself look like a beast on the streets. He grew a thick beard and wore his hair long. The head of the narcotics unit grew up hunting, and he knew about camouflage. If he was going hunting on the streets of Greenville, he knew he had to make sure his prey didn’t spot him. He rode with a ragtag group of professional cops and adrenaline junkies moonlighting from their day jobs in the square world. He and his partner Miles Cheatham conscripted John Belk, a finance man from General Motors, and Ken Pettus, a football star turned Furman University football coach. They went bird hunting together. They cooked out before going out for busts. They were the first of their kind in Greenville County, South Carolina. At the start of the drug war in the 1970s, their unit was brand new, and by default, an elite operation bent on ridding a troubled county of one of its many big problems.

John Belk

John Belk

Miles Cheatham

Frank Looper

It might have sounded ruthless, but to Looper, it was just part of the hunt. When it came time to move in for the kill, he was more compassionate than most cops on the street or doctors in the local hospital.

CATCH & RELEASE

In the summer of 1974, Looper picked up an addict who had been dealing heroin to support his own habit. After a few hours in jail, the addict was suffering severe withdrawal, retching, sweating, and begging for help. Looper and his fellow narcs worried the man might die. They took him to the hospital, but doctors saw no medical reason to admit the patient. They gave him a shot and sent him back to jail. It wasn’t long before the addict started to get sick again.

Looper and his agents decided they only had one choice. They started calling around to high-profile members of the county government and after three tries got the hospital to agree to admit the man.

It backfired.

Before the intake work was finished, the addict walked away from the hospital and the unsympathetic doctors at the Mental Health Center. Looper believed his prisoner was tired of the doctors saying he was going to be fine when the man felt sure he was going to die. One doctor said, “Heroin withdrawal doesn’t kill…He was in no medical danger whatsoever…Just picture a bad case of the flu and intensify it.”

“He got tired of hearing that junk,” Looper said.

Looper saw an opportunity for compassion, one made easier by the fact that the addict got his fix and turned himself in at the jail less than 24 hours later.

“He needed relief. He went back out on the street and got the one thing he knew would end his pain,” Looper said. “He wasn’t hurting when he turned himself in.”

Barely half a year would pass between the night Looper defied doctors and reached a hand out to a street junkie and the afternoon someone put a bullet behind his ear. He died with a reputation as untarnished as his future had been bright.

In an unsigned eulogy in the local paper, an undercover cop wrote, “Those who knew him best will tell you that he is sometimes short-tempered. However, these same officers will tell you that his integrity and honesty are beyond reproach.”

Sheriff Cash Williams, Looper’s boss, put a finer point on it.

“I don’t believe we’re going to be able to measure the loss,” Williams said. “He was a fine young man dedicated to the eradication of drugs in Greenville County. He felt if we could eliminate this problem, a lot of other things would fall into place.”

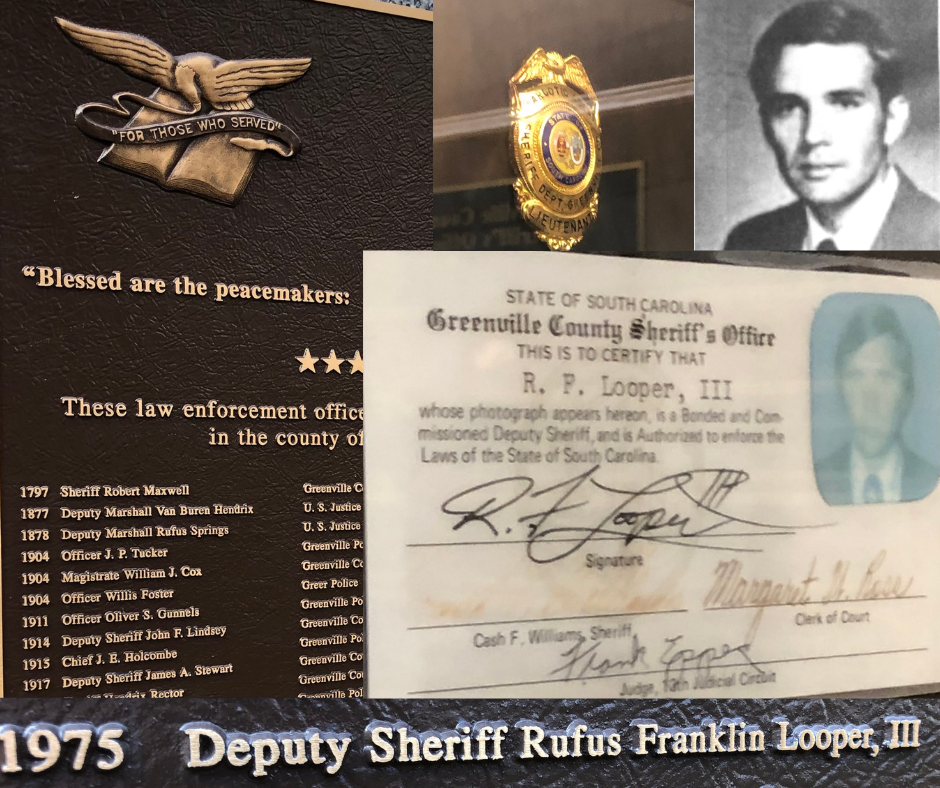

From fresh-faced to fuzzy beast

It was hard to imagine how the young clean-cut kid with the flat top from Greenville High School had turned into a long-haired man with a scraggly beard who knew more about the city’s underworld than almost anybody in town.

Less than 20 years earlier, Frank Looper had been a kid in GHS’s Trade and Industry Club where he learned the same auto mechanics tricks his dad used at the shop. He was small with a crooked smile. He hung out with the school Pep Club, and when he graduated in 1959, his peers described him as a “rare compound of loyalty, frolic, and fun.”

Though he would someday be one of its most notable alumni for the most tragic reasons, Looper shared the hallways of Greenville High School with people who he’d know in another life. Johnny Mack Brown was a football star for the Red Raider football team who would go on to be Greenville County Sheriff and create the Frank Looper Deputy of the Year Award.

Johnny Mack Brown

Frank Looper

Billy Wilkins, the man who would go on to prosecute Frank Looper’s murder, was one of Greenville High’s most promising students, one who eventually became one of the most respected legal professionals in South Carolina.

Nevertheless, Frank Looper did not take a path directly to the police academy like a lot of the young cops from that era. He went to Greenville’s Furman University and then to the United States Navy. Nearly a full decade of his life passed before he found his way into law enforcement. He wanted to go to work for the U.S. Customs Service, but his eyesight wasn’t good enough to do the job without glasses.

Eventually, he found his way to a local defense attorney who needed an investigator. It got him noticed in law enforcement circles, and by October 1971, he’d gone to work for Sheriff J.R. Martin as part of a narcotics unit.

Looper grew his close-cropped hair long and stopped shaving. He went undercover into Greenville’s underground, looking for dealers and making busts wherever he could. His fellow narcs looked at him and dubbed him “the fuzzy beast.”

Looper was unstoppable. Though he may have looked like a longhaired junkie, he was instead the type of guy who left no detail out of his reports. He was religious about complete case files. He trained himself to work for two days on no sleep, the dual schedule of his undercover personality and the cop working to bust the people who looked like him.

It wasn’t long before Looper’s name was showing up in The Greenville News associated with high profile drugs busts and drawing the attention of the city’s top prosecutor. In June 1972, Solicitor Thomas W. Greene hired the fuzzy beast as his criminal investigator for the 13th Judicial Circuit.

Drug war soldier

In 1972, there was political capital in fighting drugs. After years of relaxed attitudes toward marijuana, the United States began to undergo a shift in attitude, one driven at the federal level by President Richard Nixon. Though it never developed the same reputation as California or Florida, South Carolina became a major port for the drug trade as a group of so-called “gentlemen smugglers” turned the South Carolina coast into a major drug port.

In addition to drugs coming from other countries and landing on the South Carolina coast, small-time growers in Upstate South Carolina were working to maintain that region’s reputation for underground trade. Not too many generations had passed since the moonshine runners of South Carolina’s dark corner had controlled the local liquor racket. The product might have changed, but there was still good business to be done growing weed in the mountains north of I-85. Frank Looper and prosecutor Thomas Greene aimed to change that. Over the next year, Looper appeared in the newspaper over and over, at times standing in his suit and tie holding up marijuana plants taller than he was. In the fuzzy beast’s place stood a man who looked more like a federal agent who was responsible for a drug bust worth three-quarters of a million dollars.

As 1972 turned into 1973, Looper’s responsibilities at the Solicitor’s Office took him farther afield. He busted up liquor stills like a modern day Eliot Ness, taking axes to gallons of illegal hooch in front of newspaper photographers. He investigated porn shops and dealt with the daily drudgery of life inside the prosecutor’s office. It wasn’t street work, but it cemented Looper’s reputation with local lawmen.

By the time the War on Drugs was taking hold across America, Frank Looper had established himself as the man to lead the fight in Greenville, and the county’s new Sheriff wasted little time in turning Looper into his top drug cop. By October 1973, Looper had quit the Solicitor’s office and gone to work as Sheriff Williams’ lieutenant in charge of drug investigations.

Looper hit the streets hard and left no question what his intentions were. When the newspaper asked him if relaxed attitudes toward drugs nationwide had changed anything in his approach to enforcement, he didn’t equivocate.

“As long as it’s against the law, we will arrest people,” Looper said. “Although our main concern is large quantities and distributors, we won’t overlook simple possession if it’s a flagrant violation.”

In 1974, Looper’s six-man narcotic squad made 257 drugs busts for the Sheriff’s Office. The more busts he made, the more his stock rose in the Sheriff’s Office and with the local press. In just a few years, Looper had transformed himself from an aimless veteran to the media’s go-to cop. The reboot of “Police Story” had debuted the previous fall and had harnessed the public’s fascination with gritty police work. That was the fuzzy beast’s brand in trade.

“I believe the program portrays police work more realistically than any other similar program,” he told the newspaper. “There is no comparison between the authenticity of the program and others presented previously.”

While Looper may have turned himself into a media hero in a suit, he hadn’t changed on the street. One fellow undercover officer would eventually write, “Many of the younger generation did not realize that Looper was interested in their welfare and often mistook his ‘lectures’ as harassment. And sometimes, because he was a hard-nosed police officer, he would react with a display of emotion and engage in a heated verbal exchange with those he wanted to help.”

His boss was no less effusive in praising his top narcotics cop. Sheriff Cash Williams said that Looper, like any good cop, didn’t believe he was ever off-duty.

“There wasn’t any set schedule on his hours. He might work 24 hours. He might work 36 hours. In the nature of his work, it was impossible for him to have any kind of scheduled hours,” Williams said. “It’s not like a craftsman in a manufacturing plant where at four o’clock in the afternoon he goes home and forgets about it.”

Lt. Frank Looper died at 9:25am on February 1, 1975. He has been honored on memorials at the Greenville County Law Enforcement Center, the South Carolina State House, and the National Law Enforcement Memorial in Washington, D.C.

Show notes:

The surviving members of Rufus and Frank Looper’s family reckon with their own history as they remember the murders that changed their family forever. Frank Looper’s cousin, Adele McAuley, accompanies Brad Willis to the cemetery where her family rests and looks back at Looper’s life as a child who loved to hunt and counted on his grandfather to give him refuge from a complicated life at home.

The family of a volunteer undercover narcotics officer recalls how Looper formed a ragtag band of drug cops to run down Greenville, South Carolina’s drug dealers, and the loss those men experienced when Looper died.

Adele recalls her own indiscretions and what happened the night the local cops caught her doing the one thing a drug cop’s cousin shouldn’t be doing.

Looper’s family deals with the fallout of coming to believe Charles Wakefield is an innocent man, and their belief that the motives for the Looper murders rested solely in Looper’s battle against drugs in his city.

Featured interviews in Finding Frank Looper

Billy Wilkins, with son Walt (Photo: Cindy Landrum)

Freida Belk (with son, Jay)

Sheriff Johnny Mack Brown

Andy Ethridge

Julia McAuley

Adele McAuley

Scott McAuley

6 comments on Episode 2: Finding Frank Looper

Comments are closed.

Episode 2 is excellent and I can hardly wait the week until Episode 3.

This podcast about Frank Looper and Charles Wakefield is facinating. I have been a friend of Charles Wakefield for over 20 years. I met him through an email he sent to me from a library where he worked during the day. He spent his nights in a local jail. Even though I have known him that many years, we have never discussed the environs of Greenville, SC nor what it was like living on the streets of Greenville. So listening to Brad Willis unfold this story episode by episode is just riveting to me. I wish I could order the video of the film from Netflix today. I would watch it the day it arrived on my door step. I hope to do that some day soon.

Great story and podcast! I shared on Facebook tonight. Saw it mentioned on the Greenville TV news tonight and checked it out. I hope you get a lot of listeners and find out who killed the Looper men.

I moved into the house where Grandpa Looper lived when I was 15. My parents live there still and knew the Loopers well. There is an old well covering with Franks signature written in the fresh cement. The gunshots were still there when we moved in. Great podcast. Love the story. I know many of the people.

Wow, the plot thickens. Someone was definitely trying to shut Sheriff Looper down before he exposed the crimes going on in Greenville.

Billy Wilkins was really great at railroading people.

Much misery for many at the Wilkins’ hands.